The Ownership Chain – How the Securable Owner affects Permission Enforcement in SQL Server

Introduction

Over the last ten days, I have introduced you to the different nuances of securable ownership. However, there is one particular important topic that I have omitted so far: The Ownership Chain.

Ownership Chain Example

This example is going to be a little more involved, so bear with me. First, we need three users:

CREATE USER TestUser1 FROM LOGIN TestLogin1;

CREATE LOGIN TestLogin2 WITH PASSWORD='********',CHECK_POLICY=OFF;

CREATE USER TestUser2 FROM LOGIN TestLogin2;

CREATE LOGIN TestLogin3 WITH PASSWORD='********',CHECK_POLICY=OFF;

CREATE USER TestUser3 FROM LOGIN TestLogin3;

[/sql]

Next, we need a table and a view in separate schemata:

GO

CREATE SCHEMA TestSchema2 AUTHORIZATION TestUser2;

GO

CREATE TABLE TestSchema2.tst(id INT);

INSERT INTO TestSchema2.tst VALUES(42);

GO

CREATE VIEW TestSchema1.View1 AS SELECT * FROM TestSchema2.tst;

[/sql]

Finally, we are going to grant the SELECT privilege on that view to TestUser3:

[/sql]

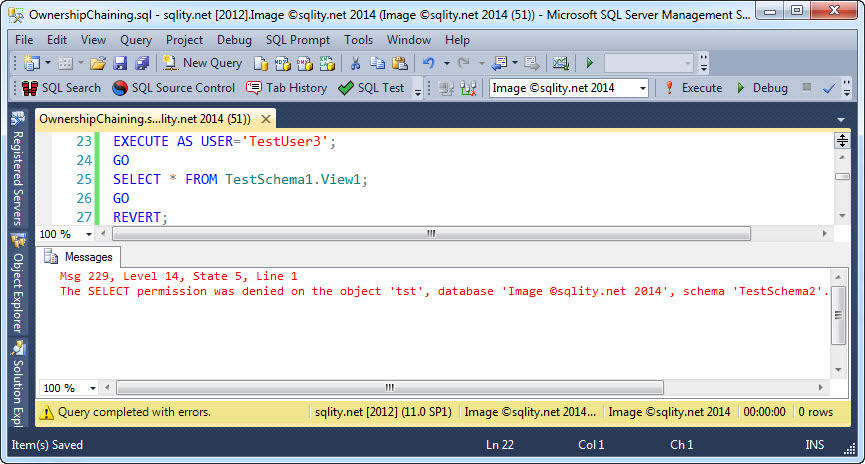

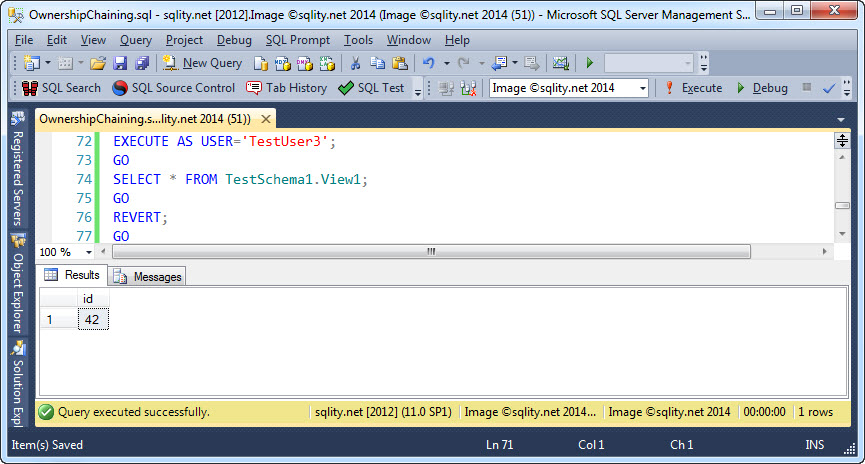

With all that in place we can have TestUser3 select form the view, right? Let us try:

GO

SELECT * FROM TestSchema1.View1;

GO

REVERT;

[/sql]

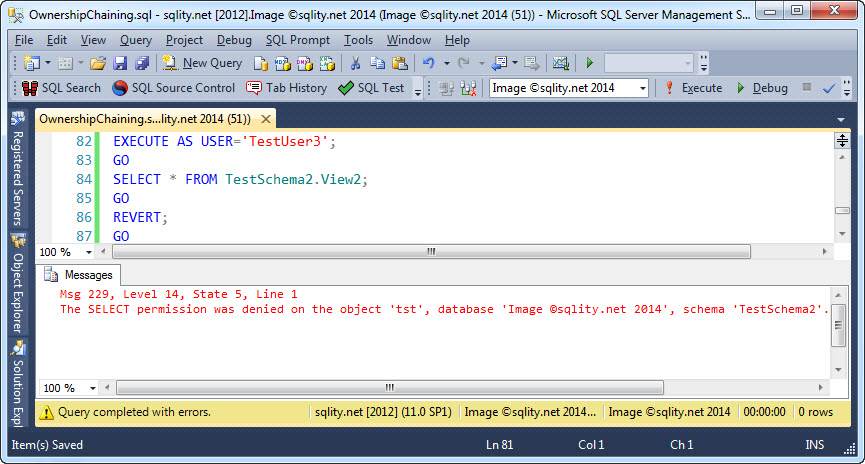

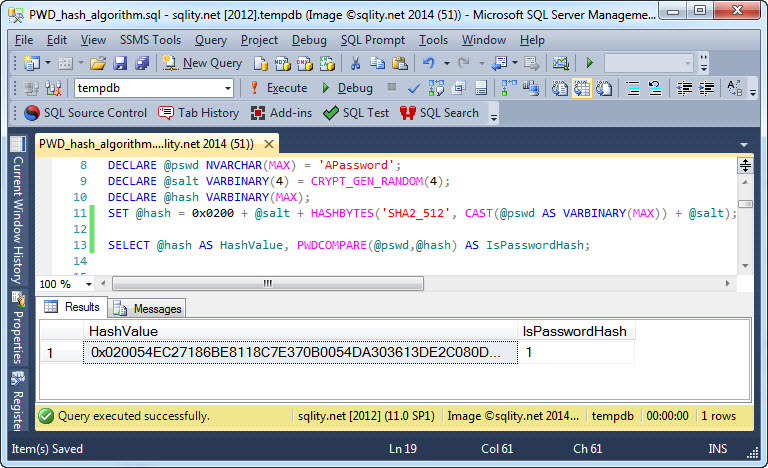

That attempt fails:

The error message clearly lets us know that TestUser3 does not have access to our table:

The SELECT permission was denied on the object 'tst', database 'Image ©sqlity.net 2014', schema 'TestSchema2'.

[/sourcecode]

But why? I always thought that using views is a good way to manage access permissions and now this.

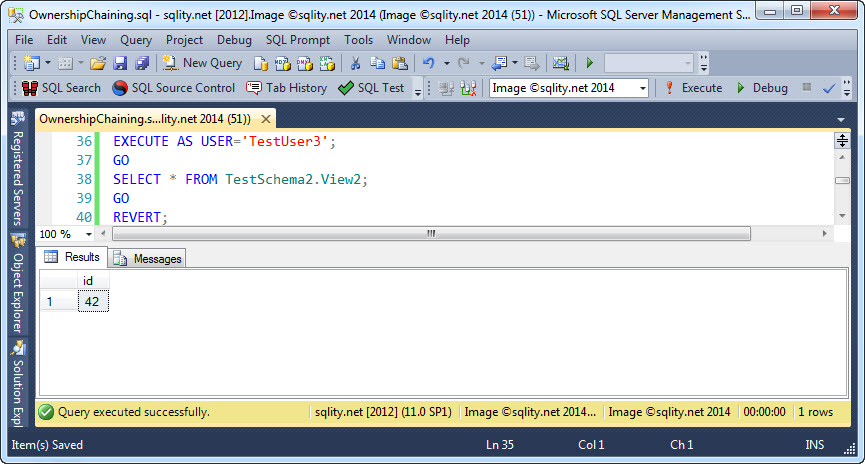

Well, schemata have not found widespread use in the SQL Server development community, so maybe using different schemata for the table and the view was not such a good idea after all? Let us create that same view again, but this time in TestSchema2, and again grant SELECT to TestUser3 on it:

GO

GRANT SELECT ON TestSchema2.View2 TO TestUser3;

[/sql]

TestUser3 can now successfully select from that new view:

However, this is not due to the different schemata used. Instead, this behavior is caused by the owners of the referenced objects, or to be more precise, the ownership chain.

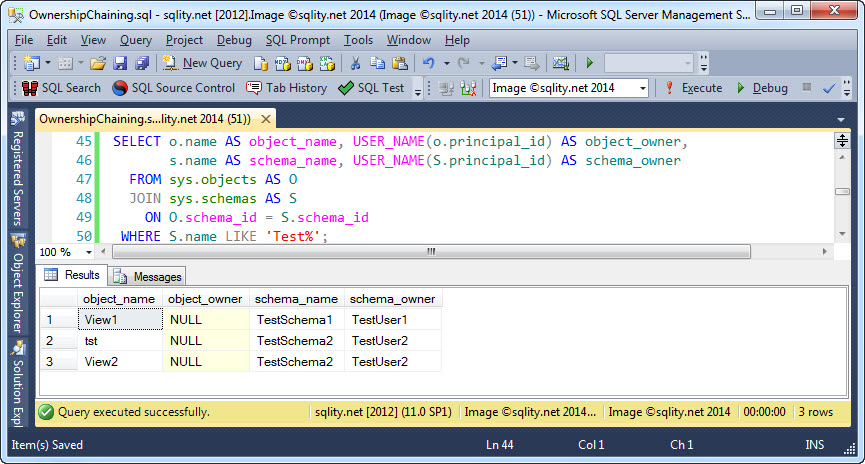

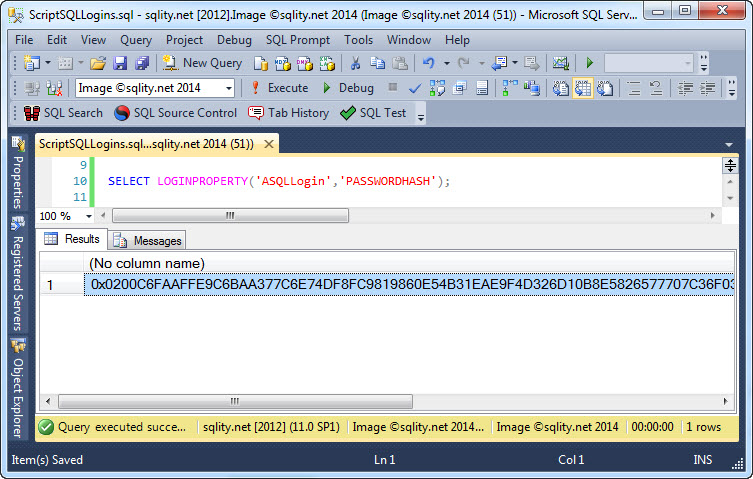

Let us quickly review the owner situation four our objects with this query:

s.name AS schema_name, USER_NAME(S.principal_id) AS schema_owner

FROM sys.objects AS O

JOIN sys.schemas AS S

ON O.schema_id = S.schema_id

WHERE S.name LIKE 'Test%';

[/sql]

It returns the object name and owner as well as the schema name and owner for each of our objects:

Remember, a NULL principal_id for a database object means, that it is owned the schema owner. That means that TestSchema2.View2 and TestSchema2.tst have the same owner (TestUser2) whereas TestSchema1.View1 is owned by a different owner (TestUser1).

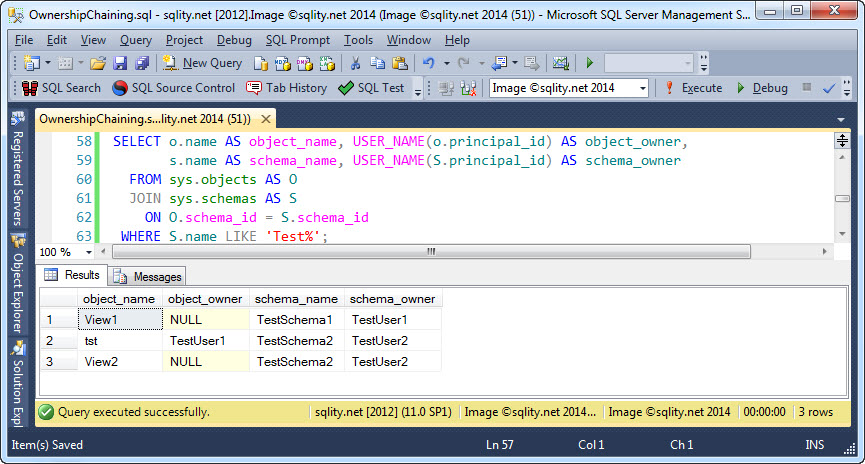

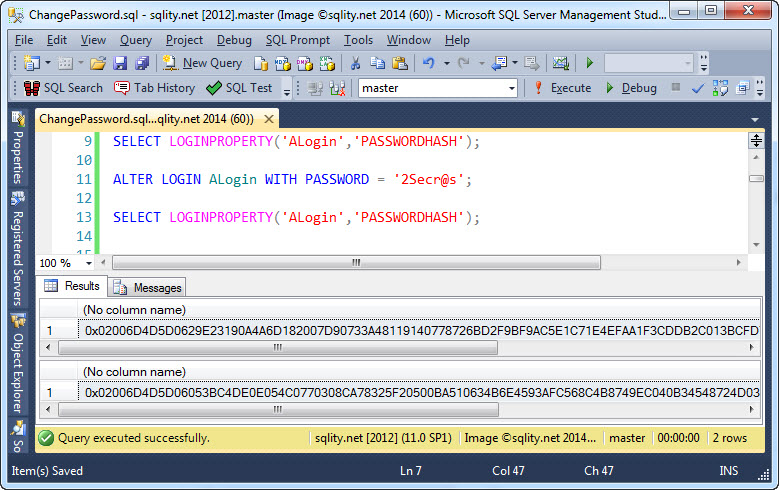

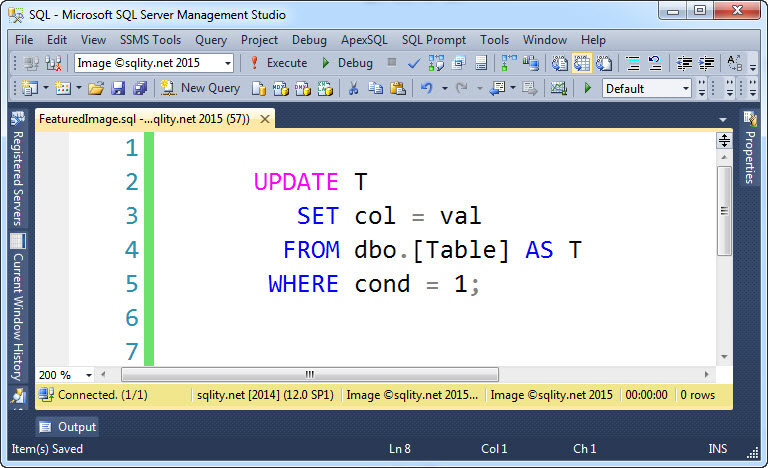

To demonstrate that this behavior is actually caused by the owner, let us change the table owner explicitly to be TestUser1:

[/sql]

To confirm the new ownership we can use the same query as before again:

Let us see what happens when TestUser3 tries to access the two views again:

TestUser3 can now successfully select from TestSchema1.View1. Remember, the only thing that changed between this attempt and the previous one is the owner of the table itself.

For completeness, let us see if TestUser2 still can access TestSchema1.View1:

As you might have expected, the access to TestSchema2.View2 is now denied.

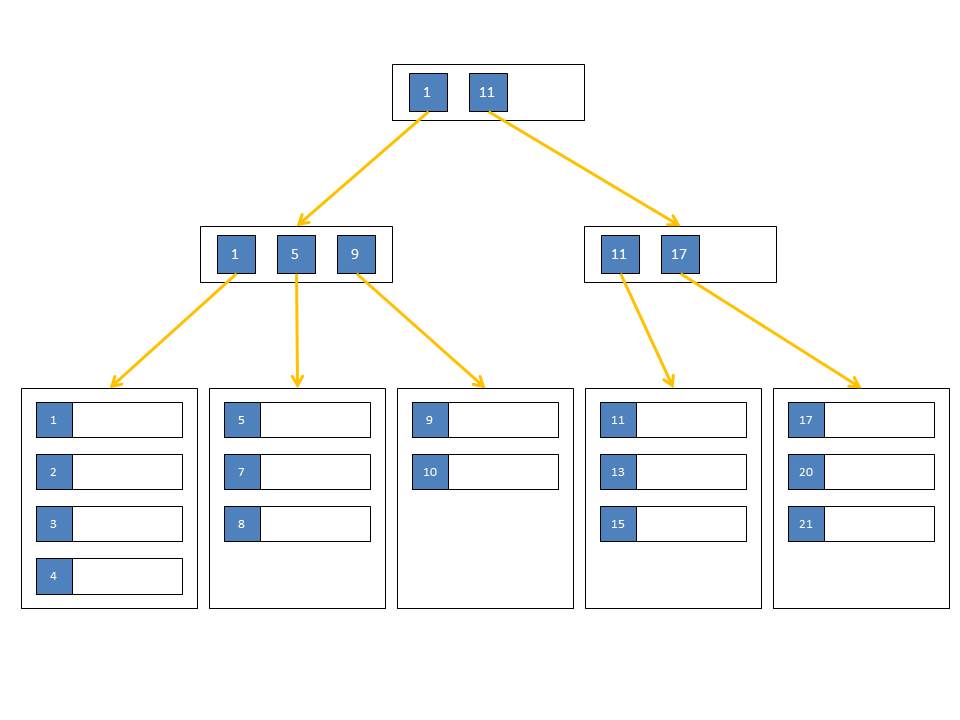

Ownership Chain Explained

When SQL Server executes a query, it checks the permissions of the executing principal on every object that is touched on the way. Therefore, if you run a select statement against a view that in turn selects form a table, you need to have access to both the view and the underlying table.

However, before checking the permissions on the underlying securable, SQL Server checks if the accessing object (the view) and the accessed securable (the table) have the same owner. If they have the same owner, permission checking on the accessed securable is completely skipped and access is granted.

Ownership chaining is a good thing in most situations, as it allows you to establish something I call guarded access. Instead of granting direct access, you can grant access to a procedure that can apply additional security rules. However, ownership chaining can also undermine you security. In some circumstances, it can for example be used to circumvent an explicit deny.

Summary

Ownership chaining describes the process of skipping all permission checks when a securable is accessed from within another securable and both are owned by the same principal. This allows for guarded access scenarios, where access to a securable is only granted through a T-SQL module that can be used to enforce additional security requirements.